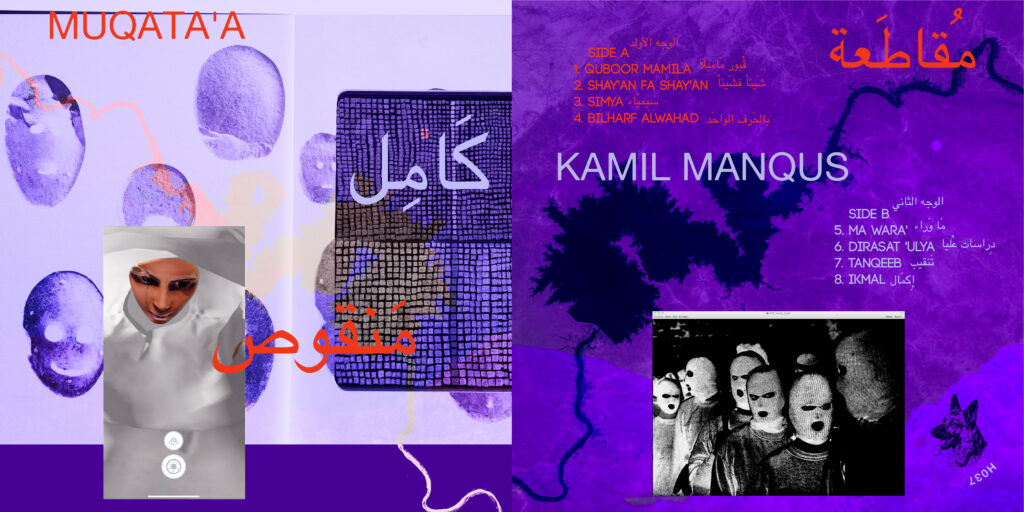

Imperfect World: Muqata’a and the Palestinian sound

With the striking identity of his hybrid hip hop instrumentals, Muqata’a offers a window into the vibrant vibrations of the Palestinian underground. Coinciding with his new album Kamil Manqus, Oli Warwick spoke to him about the realities facing his community, and how his sound responds in kind.

Pausing the present reality for a moment, in a pre-pandemic world it was very easy for anyone in the West with the right kind of passport to take international travel for granted. Simplified generalisation that might be, but true for many, not least touring artists earning their living skipping from city to city. When I connect with Palestinian producer Muqata’a in January 2021 and he mentions he’s in Berlin, it doesn’t come as a shock. Artists are always in Berlin. But for Muqata’a, it’s come about somewhat by accident while trying to make his life easier as a working musician.

“I had a bunch of performances around Europe,” he tells me. “So I thought it would be better for me to be based in Berlin to be able to travel more easily. It’s very difficult to travel from Palestine to Europe every time I have a show.”

In a globalised world, travel to the Middle East doesn’t feel like much more of a stretch than any European trip, but it’s easy from an outside perspective to forget the realities facing someone living in Palestine.

“We’re not allowed to have an airport in Palestine so we have to cross over into Jordan,” Muqata’a explains. “The border is controlled by Israel, so it takes a lot of time and it costs a lot. Even if you have your ticket, you still have to plan ahead, because at night the border is also closed. So if your flight is in the morning, you have to go a day before to Jordan. But sometimes it will take three hours to cross the border, and sometimes it takes about nine hours to cross.”

Muqata’a made it to Berlin 10 days before lockdown took hold in the German capital, and all his gigs were cancelled.

“It was really difficult,” he admits, “but it happened to everyone in the world, I guess.”

Pandemics and year-long layovers aside, Muqata’a has become an increasingly visible and urgent presence in the global melee of leftfield electronic music. His sound balances discernible, groove-oriented rhythms with abstract noise, creating something challenging but accessible. His last album Inkanakuntu came out in 2018 on Souk, a sublabel of Discrepant, which helped establish him on an international level. Within the Palestinian music scene though, he’s been a long-standing figurehead who used to be on the mic as Boikutt in breakthough hip hop crew Ramallah Underground. Their stated aim was to ‘rejuvenate Arabic culture’, drawing on their culture and situation to give voice to the reality for Palestinian people.

A vibrant hip hop scene emerged in the wake of Ramallah Underground, and alongside it other alternative scenes such as noise. Such scenes are ever-developing in Palestine, but they’ve reached maturity to the point of having a unique local slant that stands independent of similar sounds from elsewhere.

“At some point, a lot of Palestinian artists or musicians realised it’s time to develop your own sound, and not sound like you could be coming from anywhere else,” Muqata’a explains. “Of course, it was happening organically, but because of the specific situation we live in, it creates an urgency to have a specific response and a specific sound that comes out of this specific environment. So even a lot of the noise music that comes out of Palestine feels like it’s specific to there.”

On Kamil Manqus, Muqata’a new album, it’s the specific juxtaposition of sounds that holds magic and curiosity, gliding between moments of heavily processed, eerily tense abstraction and crooked, funky percussion that sounds a long way from conventional drums. Throughout though, there are passages which chime for anyone into alternative electronic music in the Western world – ‘Shay’an Fa Shay’an’s stylishly scuffed beatdowns and noirish chord drops would gel well with the weirder end of the trip hop spectrum. At one point Muqata’a rides a tear-out Amen break, albeit wringing it thoroughly through some hefty FX, on the fiery ‘Dirasat ‘Ulya’. So what exactly do genres like jungle and trip hop have to do with the sound of Palestine?

It’s worth considering the way music disseminated in the pre-internet era, especially in non-western countries. Pirate tapes were vital seeds carried in from elsewhere, duplicated ceaselessly and breaking new musical forms to hungry ears. Muqata’a and his older brother discovered hip hop via a tape of Dr Dre’s The Chronic, followed by punk, trip hop and so onwards. Interestingly, CDs failed to land in the same way due to the expense of duplication in the early days, swifty superseded by the internet and file sharing services like Napster and Soulseek. By that point a world of sound opened up to Muqata’a and he discovered jungle, drum & bass and more experimental music as well.

“I was raised listening to this music,” he points out. “Listening to hip hop just made sense to me, because everything I’m hearing from my parents and everything I’m living requires this response to the injustice that we see. Hip hop, punk and even jungle, it’s all [artists] putting themselves on the map, and saying, ‘we exist, we’re here, we’re fighting back.’ The aggressiveness of these types of music really felt close, like, ‘this is my music. This is talking about me, and it’s talking to me.’ All of these kinds of music came out of specific communities. And that’s exactly how we felt as well. We have a story to tell, and we have a sound to create.”

The advent of the internet was seismic across the world, but it held a deeper resonance in a country enduring the kind of restrictions and isolation like Palestine did and does. As well as being a valuable conduit for musical discovery, online networks became an essential means of transcending real world barriers. Now, the music scene of a city like Ramallah (Muqata’a’s hometown in the West Bank) shares an affinity with its neighbours in Cairo and Beirut thanks to decades-long connections initially forged online.

“Palestinians have always been isolated,” says Muqata’a, “because of geographical divides inside Palestine, Israeli checkpoints, the apartheid wall and all these things. In the late 90s we really developed a way of collaborating through the internet. The internet was a very important tool for us to communicate. We started to understand how to work online, so for us, a city that’s 10 kilometres away from Ramallah is no different than Cairo or even London or New York. So there was this positive thing coming out of a very negative situation.”

There’s no mistaking that Muqata’a is offering a window into his world on Kamil Manqus. Amidst the glimmers of breaks and beats, every track is enlivened by sliced, distorted and reformed snatches of radio and speech. As he reveals, the radio skits of Egyptian pop or traditional Arabic music were easily captured during studio jam sessions thanks to the FM receiver on one of his most trusted tools, the OP-1 synthesiser by Teenage Engineering. Other speech recordings were captured in the field during tense moments at border crossings and checkpoints. More than just sonic decoration for his tracks, these fragments of sound feed into Muqata’a’s interest in simya, part of the over-arching theme of the album.

“Simya is an ancient Arabic science, a spiritual science, where they would write a combination of numbers and letters to communicate with metaphysics or the unseen,” he explains. “So I played on that in a way, to say the numbers are the beats, and the alphabet was represented in the vocal elements in all of the tracks. So combining these two is like a process to try to reach the unseen, trying to communicate with the ancestors to create a perfect image of the past.”

This notion of trying to capture history has a deep resonance in the context of Palestine. As Muqata’a states, documentation of Palestinian history is in a fragile state on multiple fronts. His grandparents had to escape their home city Safad and settled in Syria after fighting drove the predominantly Arab population out in 1948, leaving behind all their cultural artefacts – books, pictures, records – in the flee for safety. For Muqata’a, communicating with the past can’t help but be political as well as emotional or spiritual.

“Because our [Palestinian] history is being erased, it’s very important for us to try to hold on to that and document it. So it’s also about creating the right image of our collective memory, which has been really tarnished and is being destroyed, bit by bit.”

I naively supposed that many of the samples across Kamil Manqus were old snatches of TV, radio and film media representing something of Palestinian history. Perhaps Muqata’a had found access to an archive from which to sample?

“Most of it is not accessible,” he laments. “The Palestinian archive of videos and, I guess, audio recordings and documents, photos and all these things, were actually stolen. They were being documented and stored in Beirut, and then at one point they disappeared. So our archive is pretty non-existent.”

Despite the dearth of documented culture and history to access within Palestine, Muqata’a has made a point of seeking out sounds wherever he can. On past releases he’s sampled from his parents tape collection, and he’s been avidly collecting Arabic vinyl from abroad. If there’s something very specific he needs though, sometimes the internet is the only place to look.

“I’ve even been using sources like YouTube, because sometimes that’s the only place you find a specific sound,” he admits. “The track ‘Simya’ has a YouTube sample of an Egyptian musician. It’s not the ideal place to sample from because of the quality, but that’s the only place I can find it.”

When faced with your own culture being erased before your eyes, it’s natural to want to grip onto it fiercely, to channel it through yourself and make an indelible statement to preserve it in the here and now. Our histories and cultures are an intrinsic part of our identity. Identity also has a bearing on the other branch to the theme that binds Kamil Manqus together as a project. The title itself means ‘whole imperfect’ or ‘perfect imperfect’, which takes on multiple dimensions in Muqata’a’s thinking. Primarily, it’s a rumination on the pursuit of perfection. On a literal, sonic level, you can sense the artist’s embrace of glitches, distortion and happy accidents as a fruitful part of the creative process, but it runs deeper than that.

“A lot of people in this materialistic world are trying to achieve perfection,” he points out, “but that is impossible. Instead of being afraid of all the errors, you can also embrace them, because they’re not just something negative. These errors are what make humans human. The whole idea of having a filtered picture presented as you in your digital persona is trying to reach perfection in a way. But I think it’s creating a lack for the person, like something’s missing. ‘Kamil Manqus’ is also playing on that, because ‘kamil’ means complete or whole, and ‘manqus’ means missing or lacking. So it’s the complete, but lacking.”

Modern society’s fixation on idealised virtual identities has ramifications in the real world, not least from the perspective of someone watching his embattled heritage being erased. Muqata’a nods to the fact cultural archiving is not especially of interest to anyone in the present moment in Palestine, as far as he is aware. His examination of this ego peril extends to the artwork for the album, which continues his long-running collaboration with Ruanne Abou-Rahme and Basel Abbas. In their design it’s easy to discern the motifs of digital communication – the glitched avatar in the device screen, the icons to convey emotions – but also a tension between the old world and the new.

Muqata’a also works with Abou-Rahme and Abbas on a multimedia project called Bilna’es (In The Negative), which functions as a kind of label and web publication working with artists including Dakn. As the title of Dakn’s track ‘In The Lack’ highlights, there’s a commonality to the themes these connected artists are exploring in their work.

It’s logical that common concepts and goals drive the work of Muqata’a and his collaborators when the environment they respond to has such a profound impact on their outlook and existence. Alternative music in Palestine has an urgent community purpose – one that reaches beyond borders into the global music conversation, where their voices can be heard. As in other countries, electronic and experimental noise music are still a relative niche in Palestinian society, but they’re firmly established as part of the contemporary cultural landscape in cities like Ramallah.

“In the early 2000s hip hop was still seen as this strange thing,” says Muqata’a, “but when they started to hear the samples we were using, and the lyrical content, people were like, ‘Oh, no, this is from here. It’s part of the community, this is our sound.’ With electronic music, that’s slowly also happening. But it’s also very diverse, which is what’s making it very interesting at the moment as well.”

Crucially though, there’s a sense of solidarity between clusters of fans and artists who would typically be more tribal in other parts of the world.

“What’s really nice about the scene in Palestine is there’s a lot of heavy support coming from the different smaller scenes. The people that would go to a noise concert would be the same people that would come to a hip hop concert, or some DJ set by someone else. So it’s very diverse, but also united, and that makes it very interesting. That’s also why you would hear, like, an MC on noise, or you would hear noise in a trap song.”

Understanding such a backdrop anchors the shape-shifting sonics of Muqata’a’s album. More than just a playfully curious exploration of processes and patchworks, it’s a vital community statement, a declaration of identity in the face of oppression, and a celebration of Arabic culture as part of a broader global exchange. It’s undeniably of its time, but also curiously out of time, and it’s as incredible as it could possibly be without falling into the trap of being perfect.