Various Artists // Documenting Sound

(Boomkat)

If lockdown music becomes a recognised mood in years to come, Documenting Sound will be my benchmark.

The run of 28 (and counting) cassette releases has been put out by Manchester-based distributor, label and online shop Boomkat – home to one of the sharpest stock selections going and respected for their thoughtful, tongue-in-cheek write-ups. Most of the releases in the series so far are deserving of an individual review, but right now we’re casting an eye back on the whole project.

“Documenting Sound is a new tape and download series from Boomkat Editions,” read a Boomkat Facebook post on May 21, “[it] will release recordings made during these last tumultuous months by an invited selection of artists from different disciplines and locations around the world.” The music is exclusively available via the Boomkat website, where you can only stream a preview before having to trust the curation and hit buy. This has led to many discoveries, some of which have become beloved headphone companions in self-reflective moments.

Curating a direct, creative response to the pandemic, Boomkat “encouraged artists to experiment with field recordings, found sounds, improvisation, spoken word, songwriting, collage – whatever felt appropriate and real.” The submitted material interprets an unpredictable moment in time in wildly-varying ways; lockdown transmissions from Kingston, Berlin, Cairo, Chicago and beyond.

The mission statement continues: “the only proviso was that the material should be recorded at home or its surroundings, without too much pre-planning or concern for conventions.” Fujiiiita’s KOMORI deservedly broke this rule, unless he actually lives in a bat-filled cave at the foot of Mt Fuji; as did Kevin Drumm, whose tape has one side based on sounds from the home of a friend he couldn’t visit.

Documenting Sound has developed in more different directions than the curators could have envisaged. There’s no specific arc to the series – which is fitting given the different response times and recovery stages around the world – and sometimes not even a traceable arc within an individual release. Akira Rabelais has chopped n’ screwed hiphop and a long monologue on one side of his tape, but innocuous ambient on the other. Others, like DJ Plead’s Middle Eastern-inspired jams, have the coherence of a normal circumstances album.

With just a couple of exceptions, like Hieroglyphic Being or 3Phaz, the dancefloor is far away from the artists’ headspace. For some, that was standard practice, for others it was an added foray into 2020’s unknown territories. The only other constant is a very loose style of sampling and spoken-word which takes in anything and everything, from conversations about daily routine (Ulla’s “Untitled”) to screeches of the Berlin S-Bahn (Lucy Railton) and a lofty quote from The Unimaginable Mathematics of Borges’ Library of Babel (Akira Rabelais’ “4”).

Vulnerable diaries of dark days lead to austere noise blasts; pure field recording (Lawrence English’s “The Only Way Out Is In”) leads to audio collages or intricate productions like Hunteress’ The Unshackling. There are tender love songs, shoegaze guitars, musique concrète, modern classical, a 25-minute, downbeat dancehall epic and techno with kicks so deep in the murk that it sounds like your next door neighbour is having a party.

The list of artists is far from a who’s who of contemporary electronic music, but rather a carefully-considered brainstorm from a crew with both ears to the ground. The blueprint was first laid down by Sarah Davachi, whose organ and harpsichord experiments were “a reflection of [her] interiorized state of being.” There have been excellent entries from the likes of Ulla Strauss, Jonnine Standish (of HTRK), housemates Perila and Special Guest DJ, or the Turner Prize-winning contemporary artist, Mark Lackey. Felicia Atkinson created an imaginary garden, Regis collaborated with pianist Ann Margaret Hogan, and Laila Sakini worked with delicate breakbeats. There’s a lot to take in, and this is just scratching the surface.

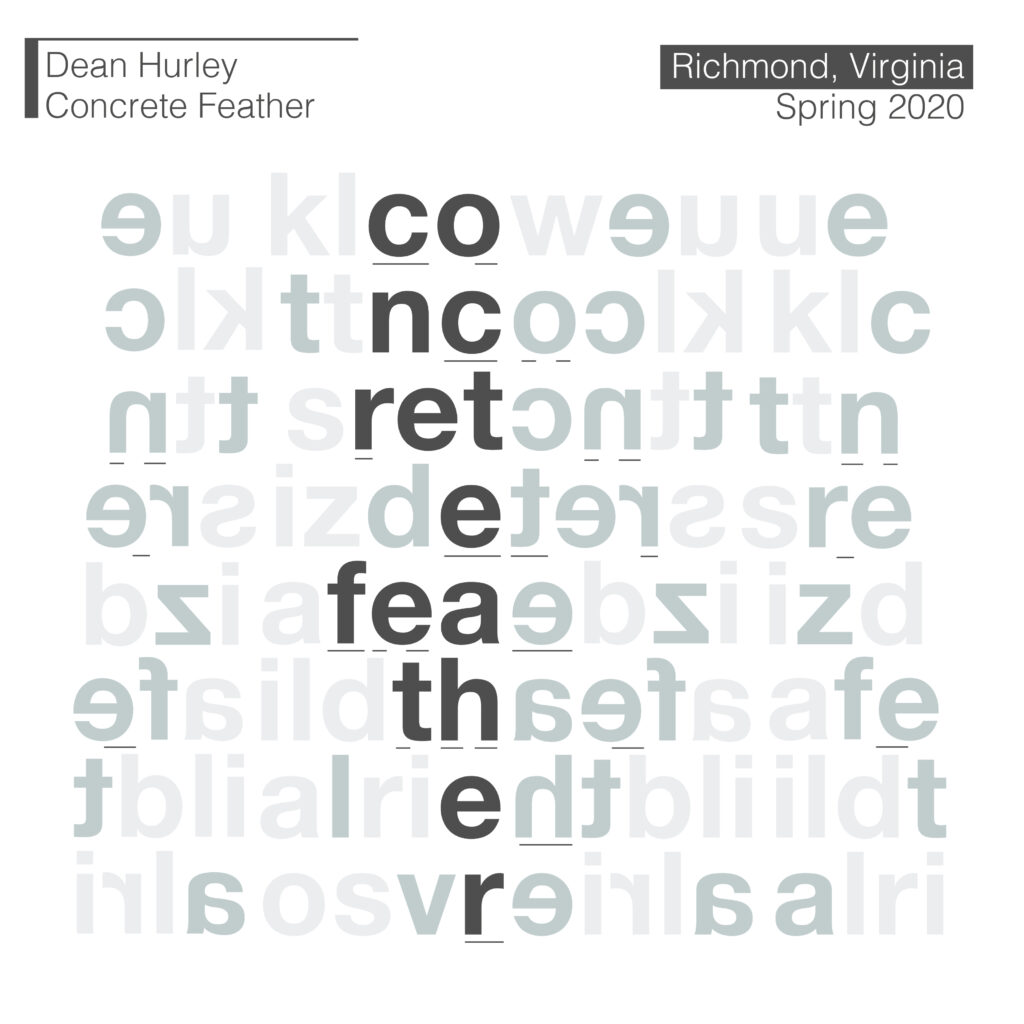

For many, the creation was primarily about listening; paying attention to those sonic fragments only perceptible in a state of heightened awareness. Dean Hurley, a sound designer for Twin Peaks, wrote about his contribution: “in a sense you’re always documenting the time you’re moving through, so when you reach for raw material to make something larger, it’s deeply reflective of where you’ve been, what you’ve been through and who you are.”

For Lawrence English, the focus was less on who we are, but how we react. He contextualised his Documenting Sound contribution, writing that the fast-changing world now requires “radical positions of thought, of generosity, of optimism and of course, radical listening, as the world’s whispers rise in amplitude.”

It goes without saying that a series with such a genuinely experimental concept will not always hit the mark, but to scan the series for any misfires would be to miss the point. In a year which will be remembered for the lowest lows and highest highs, Boomkat’s Documenting Sound series has been a highlight.